13,700,000 km^3

Maarten Vanden Eynde, Plastic Reef, 2008–12 (installation view)

Photo: Panos Kokkinias

Participating Artists

Curator

13,700,000 km3

Text by Katerina Gregos

The summer exhibition at Art Space Pythagorion takes as its cue the symbolic location of the venue and particularly the view from the main window of the exhibition space onto the Mediterranean Sea. The view of the sea assumes a central position in the architecture of the building as well as the exhibition space. Through the windows, visitors gaze at a vast expanse of deep turquoise waters, reminiscent of holiday brochures. On the beach, holidaymakers sunbathe nonchalantly, while the flight path of numerous charter flights from and to colder climates passes right over their heads, as the airport is a stone’s throw from the picturesque harbour of Pythagorion, reminding us of the ever-increasing phenomenon of mass tourism. An image of stereotypical Greece: sun and sea, and carefree holidays. On the surface, the scene appears idyllic and serene; however, the multiple invisible dynamics at play — geopolitical, environmental, cultural, religious, and economic — tell a different story. Across this “Big Blue” expanse, a host of critical issues are being played out. The sea functions here as a kind of an invisible liquid screen, a buffer between imagination and reality, paradise and dystopia.

Rainio & Roberts (Minna Rainio & Mark Roberts)

How Everything Turns Away, 2014 (installation view)

Photo: Panos Kokkinias

Depression Era

The Tourists – a campaign, 2015-ongoing (installation view)

Photo: Panos Kokkinias

Rainio & Roberts (Minna Rainio & Mark Roberts)

How Everything Turns Away, 2014 (installation view)

Photo: Panos Kokkinias

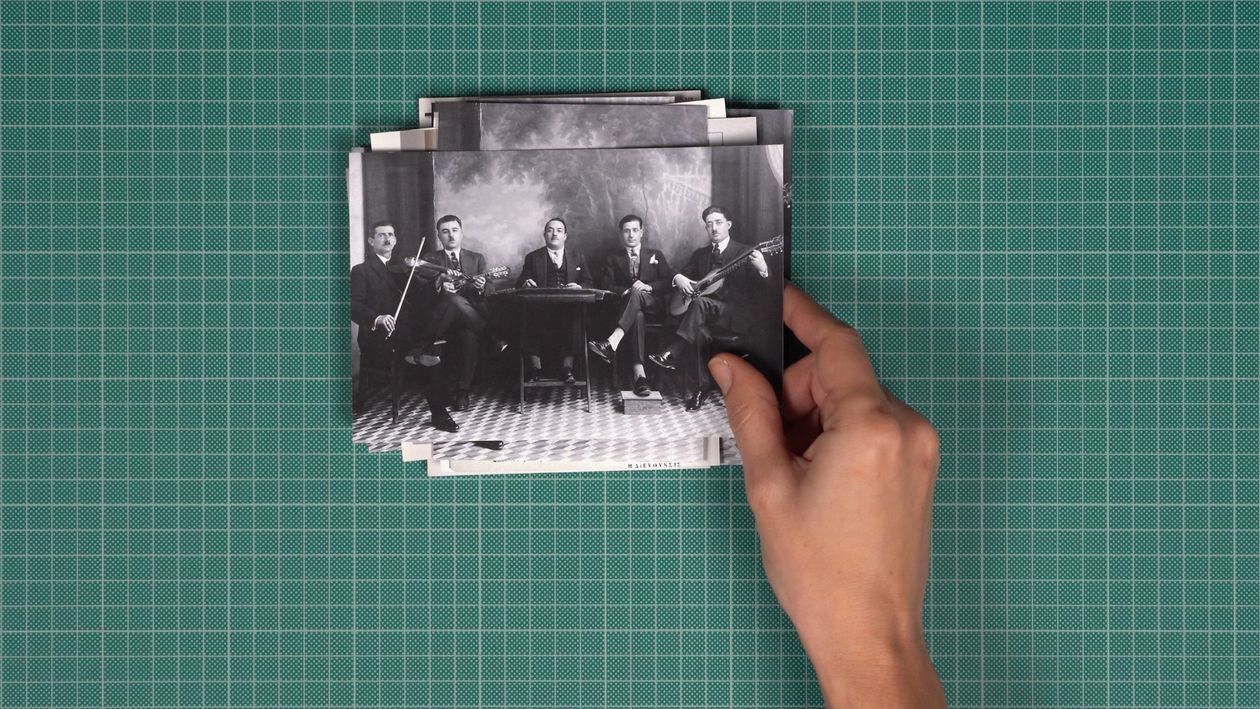

Depression Era

The Tourists – a campaign, 2015-ongoing (installation view)

Photo: Panos Kokkinias

The Mediterranean region was — and still is — an extraordinary melting pot in the history of humanity and civilisation: Numerous wars, conquests, and expeditions have taken place in — or because of — its waters, and it has been the epicentre of commercial, artistic, and cultural exchange between different peoples, shaping the identities of the countries around its shores, and beyond. In antiquity, it was a centre for knowledge production — the so-called “cradle of civilisation,” home to the seven wonders of the ancient world1 and the birthplace of Christianity and Judaism. It boasts some of the world’s most historic and celebrated cities: Athens, Constantinople, Jerusalem, Cairo, Rome, Florence, Venice. The Mediterranean Sea itself (the “middle sea” or “Mare Nostrum,” as it has been called) is surrounded by 21 modern states and connects three continents, forming an essential part of their economies. It exists as a shared resource, a space of coexistence between these countries, the one place where they are asked to find a “common ground.” The most prominent historian of the Mediterranean, Fernand Braudel went further, defining the space as the “Great Mediterranean,”2 which extends to include Transalpine Western and Northern Europe, the Mashriq and North Africa, right down to the Sahel zone. This is due to the fact that trade, goods, and people were, and still are, on the move on these transcontinental routes, in this wider “Euro-Afro-Mediterranean area.” The entanglements between Africa, Arabia, and Eurasia are thus age-old as well as ongoing.

- Sunday, August 4

Film Screening Albatross (2017) by Chris Jordan at Cine Rex

- Sunday, August 4

Public Programme

Speakers- Faye TzanetoulakouArt Historian

- Kostas DamianidisNaval Architect

- Anastasia MiliouScientific Director of Archipelagos

- Guido PietroluongoHead of Archipelagos’ Marine Mammal and Sea Turtle Research

Seminar about Archipelagos' research and actions, 2019

Guido Pietroluongo

Faye Tzanetoulakou

Kostas Damianidis

Still from Albatross (2017) by Chris Jordan

Seminar about Archipelagos' research and actions, 2019

Anastasia Miliou

Seminar about Archipelagos' research and actions, 2019

Guido Pietroluongo

Faye Tzanetoulakou

Kostas Damianidis

Still from Albatross (2017) by Chris Jordan

Seminar about Archipelagos' research and actions, 2019

Anastasia Miliou

Seminar about Archipelagos' research and actions, 2019

Guido Pietroluongo

Art Curatorial Residency Programme

The art curatorial residency programme is a Schwarz Foundation initiative aiming to bring together young professionals from different fields of science and art. Participants acquire professional experience by actively working together with internationally acclaimed art curators. In the inspiring ambiance of a historic and cultural area of high geographic importance, residents work at a freshhold between West and East. Residents meet, interact and develop ideas and references to an extensive community. The residents actively participate in the curating and production of the Art Space Pythagorion exhibition under the curator’s guidance. The production of complementary side-events, such as opening activities, lectures, workshops, educational programmes for children and screenings also fall in their line of work.

- Adriënne van der Werfresident curator

- Christina Botsouresident curator

- Georgia Liapiresident curator

- Myrto Kakararesident curator

Education Programme

Culture education is one of the main goals of the Schwarz Foundation. Each exhibition presents a specially designed education programme. In the context of the exhibition 13,700,000 km3, the education programme titled “Water Calculation” will take place at Art Space Pythagorion. The programme is aimed at high school and lyceum students as well as primary and secondary school teachers. It will take place at the beginning of the school year alongside seminars for teachers.

Designed and prepared for the fourth year by Katerina Zacharopoulou, this year’s education programme is based on both the title of the exhibition — a number — and the content of the works which were created following extensive research and analysis of statistical figures that illuminate the urgent issues of the Mediterranean Sea.

CURATOR OF EDUCATION

Katerina Zacharopoulou

Exhibition Partner

Press

- Deutschlandfunk Kultur, Werner Bloch, Vom Liegestuhl aus die Probleme der Welt im Blick (DE)

- Der Tagesspiegel, Werner Bloch, Korallenriffe aus Plastik (DE)

- Monocle - Monocle Minute, Isle be back (EN)

- Kathimerini, Maro Vasileiadou, Μεταξύ παραδείσου και δυστοπίας (GR)

- Inside Story, Alexandra Koroxenidi, Η Μεσόγειος κάτω από τον φακό της τέχνης (GR)

- Culture Now, Faye Tzanetoulakou, Κατερίνα Γρέγου: Η τέχνη μας θυμίζει να ξαναδιεκδικήσουμε τον χρόνο για να κοιτάξουμε και να σκεφτούμε (GR)

- Culture Now, Το Ίδρυμα Schwarz γιορτάζει 10 χρόνια στη Σάμο! (GR)

- EfSyn, Paris Spinos, Ηλιος, θάλασσα και γεωπολιτική (GR)

- Avgi, 13,700,000 km3 στο Art Space Pythagorion / Με θέα τη Μεσόγειο (GR)

- Alpha Free Press, Giorgos Zacharis, Αρχιπέλαγος: Μια σημαντική πρωτοβουλία (GR)

- Naftemporiki, «13,700,000 km³»: Πρωτοποριακή εικαστική έκθεση στη Σάμο (GR)

Exhibition Brochure

Credits

- Concept/Curator: Katerina Gregos, Assistant curator: Ioli Tzanetaki, Partner: Archipelagos Institute for Marine Conservation, Installation & AV: Yorgos Efstathoulidis (Constructivist), Transport: MOVEART, Media Relations: Fotini Barka, Zuma Communications, Graphic Designer (education programme): Zozi Frangou, Assistants: Evangelia Vakiarou (Education Programme), Vasileios Pristouris (Media Relations).

Acknowledgements

- Special thanks to: Anastasia Miliou and Dr. Guido Pietroluongo (Archipelagos) | FRAME, Finland (Raija Koli, director).

- Sphinxes would like to thank: Kostas Damianidis, Petros Sofianos, Yorgos Kiassos, Andreas Karamaroudis, Georgia Papadimitriou, Stelios Markou and Matrona Ktistou.

- The architectural structure of Depression Era has been made possible due to the generous support of Yorgos Efstathoulidis (Constructivist).

- The project of Kyriaki Goni, Networks of Trust, is a commission by The New Networked Normal partners (NNN). The New Networked Normal explores art, technology and citizenship in the age of the Internet, a partnership project by Abandon Normal Devices (UK), Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB) (ES), The Influencers (ES), Transmediale (DE) and STRP (NL). This project has been co-funded with support from the Creative Europe programme.