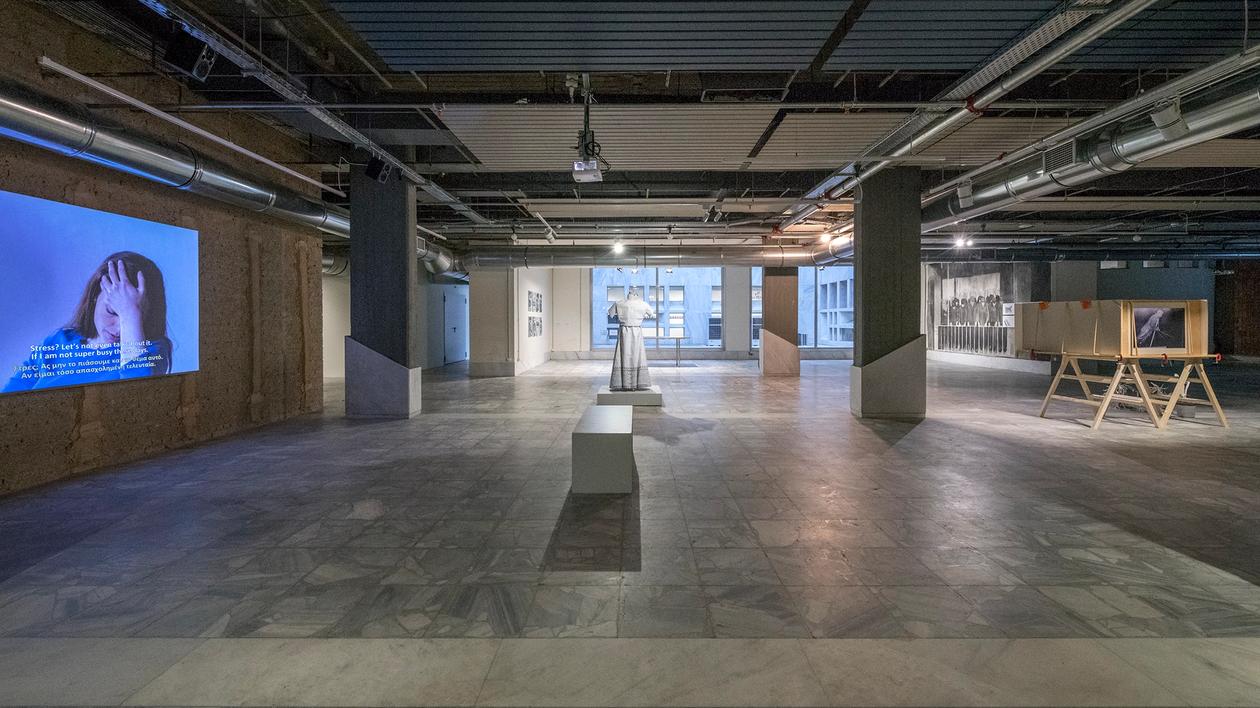

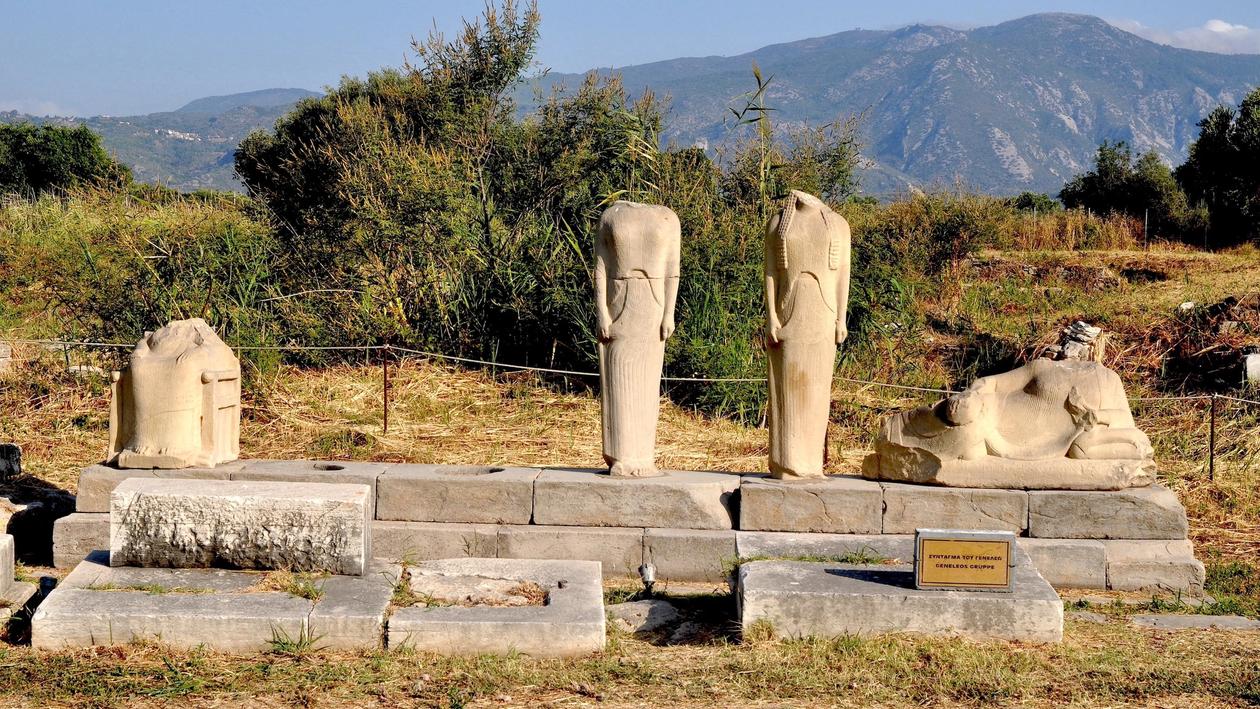

Borderline

Nevin Aladağ, Line of carpet (serial), 2014 (installation view)

Photo by Stathis Mamalakis

Artist

Art Space Pythagorion, a former 1970s hotel converted in 2012 into an arts and culture venue, lies on the seashore of Samos, 1.2 kilometres from Turkey. A large window in the main room offers views of the Turkish mainland. The “other” side is so close to Greece that you can discern the cars going up and down the hills and the trees moving as the wind blows. Even though constructed obstacles have often been erected between the two communities, the urgency of working together for a common intellectual purpose is increasingly necessary.

Beeline, 2014 (installation view)

Photo by Stathis Mamalakis

1430-m fishing rope, 15 wooden coils, photo by Stathis Mamalakis (1)

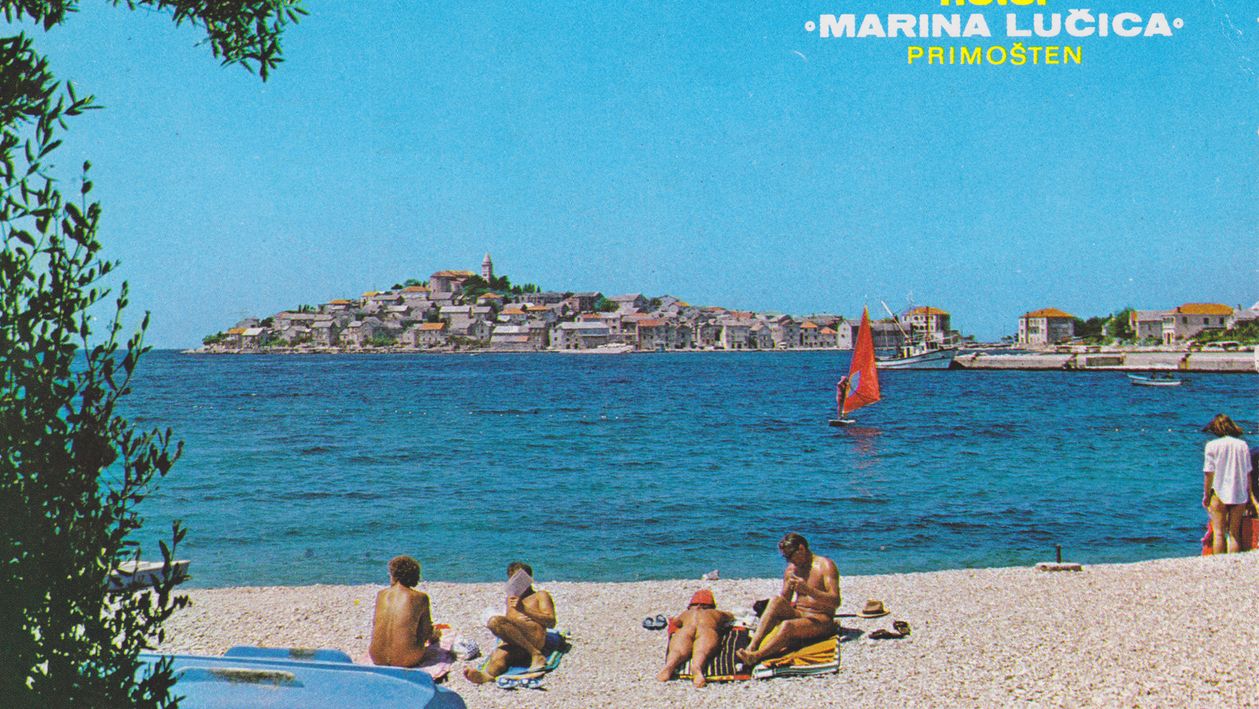

Samos is one of those politically, culturally and historically dense “vacation havens” often found in Mediterranean regions. A crucible of cultures and histories for thousands of years, it was where Pythagoras “the Samian” developed his theorem. It has also seen plague, piracy, war, and the rise and fall of empires. Today, Samos is a mass tourism destination as well as one of the major entry points for migrants trying to reach Europe and a better future.

The Frontex patrol is as much a part of Samos as tourist operators. For each hundred people swimming in the clear blue waters in the morning there is a number of people struggling to cross into Europe. In such a context, there are no easy solutions as all possible outcomes entail a degree of discomfort or a price that needs to be paid. Hope and despair, desire and unsettlement, violence and peace, loss and memory, redemption and order, the social and the individual: these all add to the fauna of the Samos seabed.

“Every practice brings a territory into existence...one that superimposes its own geography over the state cartography, scrambling and blurring it: it produces its own secession,” argues The Invisible Committee in the book The Coming Insurrection.1

Current history might be about false communities and calculated absences; however, art, as a kind of magical operation, always offers an exodus from this rigid version of reality. Art, as an unorthodox process of narration, brings historical identity politics under close scrutiny. Often, it not only speaks to an actual time and place, but also influences the future.

Interview with Nevin Aladağ

By Michelangelo Corsaro

MC: The show takes place in a border area, not only between Greece and Turkey, but also between Europe and Asia. What does it mean for you to show your work in Samos, facing the coast of Turkey, which is clearly visible from the Art Space Pythagorion venue?

NA: Coming to Samos for the first time, one immediately senses the invisible but still very obvious border, not only between two countries but also between Europe and the “rest” of the world. Samos being an island frequently facing the arrival of refugees by sea, and Frontex watching the sea borders—all these facts had a strong impact on me. In these moments you realize again that being born on “this” or the “other” side is just coincidence—yet it often determines everything.

You are left with this very ambivalent feeling of being on an island where during the day you see people on vacation, while at night refugees struggle to reach the shore.

MC: With regard to issues of immigration, globalisation, and representation of cultural identity, what does the notion of border mean to you? How do the geographical and psychological implications of the concept of border come together into your work?

NA: I deal with different aspects of these issues in my works. There is the question of limitation, whether imposed by society or physically, the material itself, or political conditions. Often, I try to question these to establish new reading options or redefine their meaning. In some cases, I try to realize site-specific projects as here in Samos, where I react to the geopolitical situation. As borders manifest themselves mentally, ideologically, or geographically, to name only a few ways, I try to approach the subject on many levels.

MC:Your works often seem to address the encounter between a political and a subjective experience of the body. How is your practice shaped around these two different perceptions of the body?

NA: A political and a subjective experience of the body are often intertwined, I think. Some of my works relate very much to an individual, physical experience of the self that might be parallel to, or different from what that same body can mean as a political entity. Bodies are embedded within a multiplicity of dependencies and to reveal some of them and how they interact with each other would be one theme in my work that falls within this scope.

MC: What is your perspective on the friction between modernity and tradition? How do these two concepts affect your work with regard to the way you question the notion of identity?

NA: Modernity, tradition and identity—these are three very different, complex and controversial concepts. To speak of a friction between modernity and tradition I would first need to accept the notion of modernity as such, which is not uncomplicated, and then see it as an opposing force to tradition, which might also not be true. But from a more personal experience and point of view: I was brought up in two different traditions, yet I experienced this as mainly a positive thing. I have always appreciated a state of flux, rather than holding on to one singular concept or idea of identity.

MC: What interests you most, as an artist, in your relation to the communities that interact with your work? Which challenges are still to be faced in participatory artistic practices?

NA: Communities not only interact with some of my works; they can also be part of them as in the performative works Mezzanine or Occupation, in which they play an important role. Sometimes they lend their voice, or take part in a large organized dance performance with no specific choreography, but based on the input of their own styles and moves. In that sense, the communities are able to not only be the receiver of my works, but to be part of them, too. One great challenge in participatory art practices remains: to combine all these elements in productive ways. So that, ultimately, the work explores an issue related to the social or political conditions of the people, integrates the people physically, mentally and emotionally into the piece, and finally radiates back to the community in a creative way.

- Wednesday, August 6

Panel Discussion Proximities: Symbolic Notions of East and West within Europe

- Ayhan AktarProfessor of Sociology

- Maria GeorgopoulouArt Historian, Director of the Gennadius Library

- Chus MartínezArt Historian

- Ingo Niermann Writer

- Başak TemürVideographer, Curator

- Adnan YildizCurator

Panel Discussion, Art Space Pythagorion, 2014

- Sunday, July 20

Curatorial Fellowship

Resident Curators- Yannis ArvanitisFellow Coordinator, Residency Curator

- Dimitris BaltasMedia Developer, Lighting Designer

- Michelangelo CorsaroCurator

- Jorgina Stamogianni Curator

- Saliha YavuzCurator

- Pavlina KyrkouEducator

With the kind support of:

Press

- Frieze, Tom Morton, Nevin Aladag: Art Space Pythagorion, Samos, Greece (GR)

- Domus, Filipa Ramos, Art beyond frontiers (EN)

- Artforum, David Huber, Far Sited (EN)

- South as a State of Mind, Jorgina Stamogianni, Nevin Aladağ at Art Space Pythagorion, Samos (EN)

- ArtAsiaPacific, HG Masters, Borderline (EN)

- Nevin Aladağ: Art Space Pythagorion, Samos, Greece (EN)

- Monopol, Jens Hinrichsen, Tiefes Wasser (DE)

- art, Gesine Borcherdt, Schatten im Paradies (DE)

- Popaganda, Lina Rokou, Η Nevin Aladağ και η εφήμερη διάσταση των ελληνοτουρκικών συνόρων (GR)

- Kathimerini, Margarita Pournara, Art Space στην αγκαλιά της Σάμου (GR)

- Andro, Ira Sinigalia, Στη Σάμο, με τη Nevin Aladağ (GR)

- Athinorama, Despina Zeykili, Η Σάμος μπαίνει στον καλλιτεχνικό χάρτη (GR)

- Proto Thema, Iliana Fokianaki, Σάμος: Πολιτικός μινιμαλισμός στο Ίδρυμα Schwarz από Τουρκάλα καλλιτέχνιδα (GR)

- Proto Thema, Iliana Fokianaki, Turkish-born Nevin Aladağ’s “Borderline”, a bridge between Samos and Karlovassi (EN)

- kar, «Μεταξύ Τουρκίας και Ελλάδας υπάρχει αλληλεγγύη» (GR)

- To Vima, Η Σάμος «συναντά» την Τουρκία στο Art Space Pythagorion (GR)

- Huffington Post, Dimitris Machairidis, Découvrez en bateau les musées et les saveurs de l'Egée du nord (FR)

- clevernews, Mε μεγάλη επιτυχία πραγματοποιήθηκαν οι φετινές εκδηλώσεις του Ιδρύματος Schwarz στη Σάμο (GR)

Download

Credits

- The exhibition is organized by the Schwarz Foundation Founders: Chiona Xanthopoulou-Schwarz and dr. Kurt Schwarz Artistic director: dr. Andrea Lukas, Exhibition Curator: Marina Fokidis, Exhibition Architect: Peni Petrakou, Schwarz Foundation: Helena Kageneck, Iason Konstantinou

- Communication Strategy, Sponsorship and PR: Dimitra Kouzi Press and Communication Consultants (Greece): Chara Zouma, Semi Psilogianni, Press and Communication Consultant (Germany/International): Anna Wichmann, Graphic design: Alexandra Rusitschka, Copy editor: Hannah Adock, Dimitris Saltabassis, Greek translations: Dimitris Saltabassis, Invigilators: Dennis Bugdoll, Evangelia Vakiarou

- All works: Courtesy the artist Nevin Alada WeNtRUP gallery, Berlin, and RAMPA gallery, istanbul

Media Sponsors